I won’t let complicity look me in the eye and hand me my degree

A personal account of navigating Western academia while confronting privilege, censorship, and the ongoing genocide in Gaza.

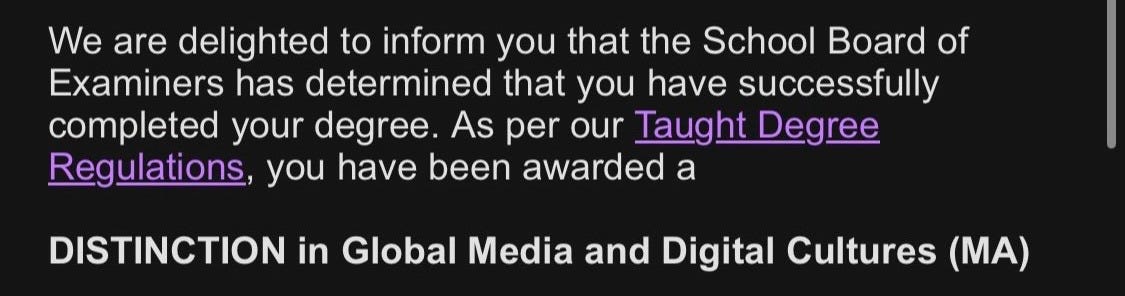

Last July, I finished my Master’s degree at one of the UK’s so-called “world-leading” universities.

One year and nine months out of two. Six hundred forty out of eight hundred ten days. Fifteen thousand three hundred sixty hours out of nineteen thousand four hundred forty. Nine hundred twenty-one thousand six hundred minutes out of over a million. Time spent reckoning with, and sitting with, the crushing weight of the privileges I hold: a roof over my head, stable internet to connect me to professors, colleagues, the wider world, food to give me energy, a family that is safe, cheering me on. Meanwhile, just 3,787 miles away, people in Gaza, including children and babies, are being ethnically cleansed and starved. If they weren’t having their schools deliberately bombed, they were watching their lives torn apart, their families murdered, all of it broadcast live to the world. A world that doesn’t really care.

My thesis began by thanking my mother and ended with a distinction. Not just the thesis itself, but across all my courses.

To my mother, whose voice rose above both of our silences. You taught me to root myself in values that neither falter nor bend and to carry compassion even when the world tempted me to abandon it. From you I learnt to always stand against injustice, to confront those who seek to silence and oppress, and to stand tall even when fear clutched at my throat. I can still remember the moments when my hands trembled and my voice faltered, yet you stood firm beside me, urging me to speak up, to rise above. You saw the light in me when I couldn’t, and through your strength, I found my own. You have been my greatest teacher, my fiercest defender, and the source of my courage to dream, proving to me that a woman’s mind is boundless, no matter what barriers the world may attempt to build around us. As your name, Sahar, so beautifully means — the first light of dawn that pierces the darkness — you have always been the light of my sky and the reason I rise, again and again.

And, to my region, the place my soul calls home, the place my heart aches for every single day. To be Arab is to carry the weight of this collective pain, to endure wounds that never seem to heal, yet still give, love, and open our hearts to one another. This work is for the unbroken spirit that defines your people. In the words of Julio Numhauser:

“The superficial changes. Depth changes. Thinking changes. Words and worlds change. But my love, no matter how far I am, the memories and the pain of my people, those do not change.”

I wrote this acknowledgement months before I began working on my thesis. I needed it as a compass, a guiding principle, because I knew exactly what I wanted to study: Israel’s propaganda machinery targeting people in the West. I believed I could do it. My university claimed to “challenge perspectives” and “empower students to question the status quo.” I mean, that was their mission. That was how they described themselves publicly. That was why I picked this university.

But there was a before October 7th, 2023, and an after.

My focus had always been on Palestine/Israel, and I had consistently been at the top of my class. Then after October 7th, suddenly, I began facing systematic setbacks in assignments in every course. Essays on other Middle Eastern countries, like Saudi Arabia, Egypt, or Iran, consistently received higher marks. Any essay that explored Palestine/Israel was met with a long list of vague feedback: “you have to be objective, neutral, grounded.” Neutrality, in my experience, is often a myth designed to uphold oppressive practices and maintain the status quo. But, I could swear, I applied the same rigorous methodology and frameworks I had used for every other essay. Yet professors who once encouraged critical engagement began insisting on “balance,” which in practice meant: don’t bring up Israel whatsoever.

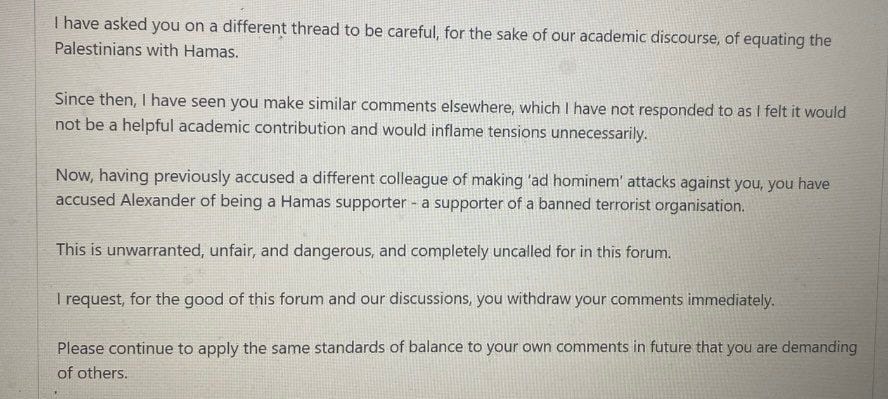

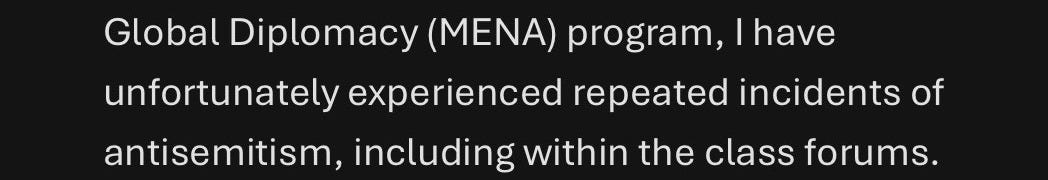

Seminars and forums became curated spaces where Israeli students could derail conversations, provoke, even attack personally, while we were told to “stay respectful.” Respect, in that context, meant permitting the framing of students as “terrorists” for simply researching or naming Palestine, while any counter-narrative was labeled antisemitic or defamatory. Respect, in that context, meant complete silence.

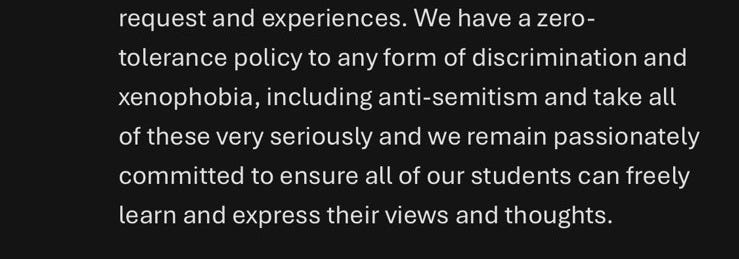

Here’s how the sequence worked: a student researching Palestine would be accused by an Israeli peer of being “Hamas.” The professor, seeking to mediate, would ask them to withdraw their comment. The Israeli student would then escalate, sending an email accusing the targeted student and professor of antisemitism and defamation. Alarmed, the university faculty would respond by sending announcements against the very students and professors who had been the original victims of harassment.

The same pattern emerged with my thesis plan. It came back with a long list of feedback. I found myself trapped in the censorship loop again, subtly but clearly constraining the study. I did not want to adjust. I wanted to prove to myself that Western academia is not the neutral, critical space it claims to be. That was the easiest path, given my demanding full-time job in advocacy and my responsibilities as the sole provider for my family. I did not want to fight invisible battles, and I am not proud of that. I kept the same research idea, the same structure, the same methodology, and simply applied it to another MENA country. The result? Perfect feedback. A distinction. I have no doubt that if I had simply changed the research back to Israel, the outcome would have been very different.

This is the architecture of academic censorship in practice. It does not always scream. Sometimes, it is just vague feedback, shifting expectations, and subtle punishments. And yet, it always works. Western academia presents itself as a neutral, critical space, but the neutrality is selective: it preserves the narratives of the powerful while systematically disciplining those who challenge them. Knowledge, in this system, is not neutral; it is political. Once a colonizer, always a colonizer, even when the empire wears a university ID badge. Suppress. Sanitize. Keep hands clean. Repeat. But their hands are never clean.

It also forces a broader, unsettling reflection: what will the historical and academic record say about this period? What counts as knowledge, whose narratives are preserved, and whose are erased? The silencing of critical research, the subtle censorship of inconvenient truths, is not just an academic failing; it is a form of epistemic violence. By privileging certain perspectives and disciplining others, academia actively shapes the archive of memory, determining which lives, which violences, and which resistances are visible to future generations. I cannot help but wonder: if these truths, are not rigorously documented, what will historians, researchers, and the world at large be left to remember, and what will they have been taught to forget?

Yesterday was my graduation. I was supposed to put myself in a plane and go receive my certificate. But I couldn’t. I cannot celebrate or feel proud in a space that feels so complicit. I cannot tell myself that the dream I had at sixteen, of this exact moment, has come true. Because, right now, there is another sixteen-year-old girl in Gaza whose chances of a future, of safety, of homeland, are being torn apart along with her home, her family, and her classmates. The same hands that would have handed me my certificate with distinction are complicit in this.

And, most painfully, my acknowledgement, the words I wrote to thank my mother, the lessons I wanted to carry forward, was thrown away. For the first time in my life, I did not apply the principles my mother taught me, the ones I had promised to pass to my own children in the future. That failure, more than any certificate or distinction, is what lingers.

You are so inspiring and I know you don’t realize how true it is. I am so incredibly proud of you and so thankful that you exist. I hope to be even 1/10th as honest and decent as you in the face of this system of death and exploitation especially these mechanisms made to ensure you view complicity and passivity as the only guarantee for personal safety. You are fucking INCREDIBLE.

I’m starting grad school in the u.s. and the neoliberal doublespeak is suffocating. I’m glad you’re out of the wolf’s mouth, and I honor your sacrifices and setbacks with my own academic commitments. Palestine will not be forgotten, not as long as I’m alive